Why unite action to stop resistant microbes

ANTIMICROBIAL resistance (AMR) is no longer a distant or theoretical threat. Across the region, we now regularly witness lives disrupted or lost because infections no longer respond to medicines that once worked.

A woman loses her husband to a previously treatable infection, a newborn dies because first-line antibiotics fail, a farmer watches livestock weaken despite treatment and clinicians confront impossible decisions when diagnostics are limited and last-resort drugs are inaccessible or ineffective.

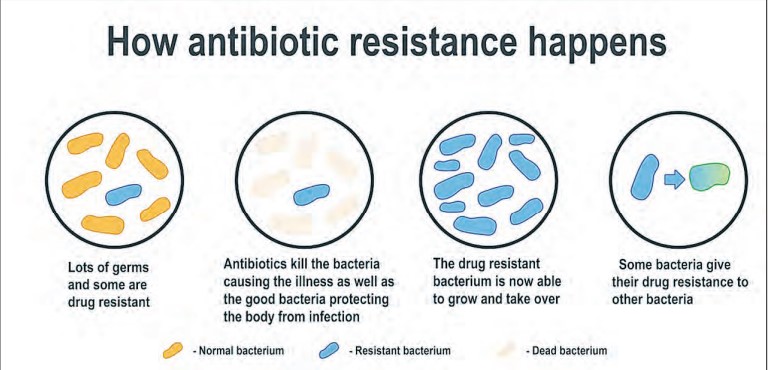

These are the lived realities of AMR—a crisis that has quietly grown into one of the most serious public health, economic and development challenges of our time. AMR develops when microorganisms such as bacteria, viruses, fungi and parasites change over time and stop responding to medicines designed to eliminate them.

As resistance increases, infections become harder to manage, treatments become more expensive and mortality rises. This is a stark contrast to what many countries experienced decades ago, when antibiotics were reliably effective and drug resistance seemed remote.

Today, across East, Central and Southern Africa, AMR is entrenched in daily life, shaping outcomes in households, farms, clinics and communities.

It is no longer an issue confined to technical reports or national plans. It demands collective action now. For many years, AMR remained “faceless”, a silent, invisible adversary slowly eroding the effectiveness of essential medicines.

The theme for World Antimicrobial Awareness Week (WAAW) 2025 urges us to “Protect today and preserve tomorrow,” reminding us that only coordinated action can secure both current health and future generations.

AMR is often mischaracterised as a purely clinical issue. In reality, it is a complex systems problem that affects health security, food safety, livelihoods and sustainable development.

AMR undermines progress toward twelve of the seventeen Sustainable Development Goals, particularly SDG 3 on health, SDG 1 on poverty reduction, SDG 2 on hunger and food security and SDG 8 on decent work and economic growth.

Resistance thrives where supply chains are fragile, infection prevention and control (IPC) practices are inconsistent, water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) conditions are inadequate, data systems are weak and the use of medicines in people and animals is poorly regulated.

No individual country, sector, hospital, or farm can stop the rise of resistant microbes alone. The scale and speed of the threat demand regional cooperation: Shared standards, comparable data, pooled expertise, coordinated investments and a unified narrative that drives decisive leadership from local to regional levels. This is where the East, Central and Southern Africa Health Community (ECSAHC) plays a vital role.

ALSO READ: TZ–Türkiye partnership boosts specialised healthcare services

Regional approaches allow countries to align methodologies, compare antimicrobial resistance and antimicrobial use data and strengthen accountability. Comparability turns scattered figures into meaningful signals that guide resource allocation, reveal trends and highlight where interventions will be most effective.

ECSA-HC’s regional Communities of Practice on AMR and IPC have built a strong foundation for collaboration. Epidemiologists, pharmacists, veterinarians, laboratory specialists, and communicators now work together instead of duplicating efforts.

Joint validation of pre-service curricula across human and animal health fosters a generation of professionals who speak the same technical language of stewardship and prevention.

Acting now requires discipline, realism and commitment. It means embedding IPC as the fundamental basis of safe care. It means using the AWaRe classification to promote rational antibiotic use, strengthening regulators to curb inappropriate sales, and investing in laboratory capacity to detect resistant pathogens early.

It requires improving the quality of data before building digital dashboards, recognising that reliable evidence is the foundation for effective action. Surveillance must translate into clear policies, budgets and implementation plans that change behavior.

Communities must remain at the centre of these efforts, because no intervention will succeed without local ownership. Protecting the present requires ensuring that frontline workers have the tools they need today. Clinicians must have access to diagnostics that guide appropriate treatment.

Nurses, laboratory staff and veterinarians must have reliable water, sanitation supplies, IPC materials, accurate treatment guidelines and ongoing mentorship. Protection also involves trust: Engaging communities, pharmacists and media partners to counter misinformation and promote responsible antimicrobial use.

When communities understand when antibiotics help and when they do not, they become active partners in halting resistance. Preserving the future demands building lasting institutions and competencies. Countries need strong accreditation systems, resilient regional networks and frameworks that ensure quality regardless of leadership changes or shifting priorities.

AMR must be integrated into broader health security and emergency preparedness agendas, as well as primary health care systems, so that financing is predictable and results are measurable. Data must be valued, not feared; evidence is the most reliable defense against both pathogens and complacency.

Partnerships and collaboration are central to sustaining progress. Multisectoral coordination must move beyond rhetoric and become a daily practice of shared learning, collective problem-solving, and aligned action.

Regional and countryto-country cooperation has already demonstrated that sectors can co-create and implement national action plans, universities can integrate AMR and IPC into their core curricula, and journalists can translate complex scientific information into compelling human stories that shift public behavior.

Every successful collaboration narrows the space in which resistance can thrive. As we observe WAAW 2025, several calls to action stand out. Policymakers and parliamentarians are urged to protect budgets for IPC, WASH, surveillance and stewardship, and to connect these investments to transparent, measurable targets.

Professional bodies and training institutions are encouraged to make AMR and IPC essential competencies rather than optional subjects, strengthening workforce capacity and promoting behavior change. Public health professionals must model infection-prevention behaviors and enable the responsible use of antimicrobials.

ALSO READ: Tanzania eyes pharma hub role

Funding agencies are encouraged to support country-owned, coordinated, and comparable initiatives because these create sustainable impact. Communities hold significant power to influence outcomes and must be empowered to act on accurate information.

The media, as trusted communicators, can help the public distinguish facts from myths and highlight real stories illustrating the consequences of inappropriate antimicrobial use.

AMR is not an unavoidable catastrophe. It is a test of discipline, coordination, and persistent commitment. The ECSA region has already shown that when countries align standards, share data and articulate a unified message, progress is possible.

Through regional solidarity and practical cooperation, we can advance safer health care, secure food systems, and more resilient economies.

Acting now protects the present; building together preserves the future. The author works with the East Central and Southern Africa Health Community (ECSA- HC) based in Arusha, Tanzania, as a Senior Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR) Control Specialist .