Tanzania’s Vision 2050: Aspirations Meet Arithmetic

DAR ES SALAAM: WHEN Tanzania unveiled its Dira ya Taifa ya Maendeleo 2050, it outlined a bold ambition: becoming an upper-middle-income country with a per capita income of at least USD 7,000 by 2050. With a projected population of roughly 143 million by that time, the implied economic target is staggering—Tanzania would need to grow its economy to USD 1 trillion in constant terms. To reach this, it must sustain average annual GDP growth between 8 percent and 10 percent for the next 25 years. The question is not whether such ambition is desirable—but whether it’s mathematically and institutionally achievable.

To appreciate the scale of this ambition, consider the following. In 2024, Tanzania’s economy stands at roughly USD +80 billion. To meet the Dira 2050 target, it must multiply more than tenfold—hitting USD 1 trillion in just 25 years. That’s like planting a mango seed today and expecting a mature orchard by next week. One missed growth season, one policy misstep, and the timeline shifts. Economic development doesn’t bend to declarations—it responds to deliberate design. Without a clear path from today’s soil to tomorrow’s harvest, the dream risks becoming a projection, not a plan. Ambition must be matched with structure, or it will remain just that: ambition.

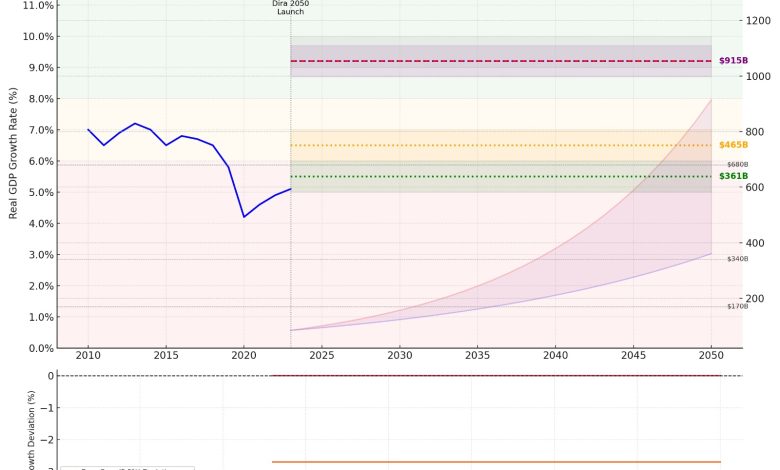

A modelled comparison of three long-term GDP trajectories—based on 5.5 percent, 7 percent, and 9.2 percent annual growth—helps illuminate what’s at stake. The base case, reflecting Tanzania’s recent growth history, leads to a GDP of around USD 361 billion by 2050. A more optimistic seven percent growth path pushes this to USD 465 billion, still far from the trillion-dollar goal. Only the aspirational 9.2 percent trajectory brings Tanzania to approximately USD 915 billion by 2049, just within striking distance of the Dira’s target.

These projections underscore what’s known as the “ambition gap.” Even small deviations from high growth—say, sustaining eight percent instead of 9.2 percent—can significantly delay the timeline or reduce the GDP outcome. This is especially sobering considering Tanzania’s real growth averaged below six percent over the last decade, including disruptions from the COVID-19 pandemic. Achieving a consistent nine percent growth rate for 25 years is not unprecedented globally—but it is exceptionally rare, particularly without a major structural shift in productivity, investment flows, and institutional performance.

To close this gap, the Dira sets out six strategic pillars: industrialization, digital transformation, human capital development, infrastructure expansion, good governance, and inclusive development. These are the right priorities in theory. However, their ability to act as genuine catalysts depends entirely on how they’re sequenced, financed, and executed.

For example, the industrial push must move from import substitution to globally competitive value chains. Infrastructure development should focus not only on physical access, but on productivity and trade linkages. Education needs to deliver cognitive, technical, and ethical competence—not just school enrolment. Digital growth must reach rural economies, integrate the informal sector, and connect citizens with state services. And most importantly, governance must move from slogans to delivery—with accountability systems, performance tracking, and institutional transparency at the centre.

This distinction between goals and delivery mechanisms is where many national visions falter. To understand how Tanzania might avoid this pitfall, it’s worth looking outward. Countries like Rwanda, Malaysia, and Ethiopia have each pursued long-term transformation strategies—and their contrasting results offer valuable lessons.

ALSO READ: ‘Vision 2050 to redefine TZ’

Rwanda’s Vision 2050 is grounded in phased implementation frameworks, monitoring dashboards, and policy consistency across administrations. Malaysia’s Vision 2020, while it missed its income target, still transformed industrial capacity and human development outcomes through public-private investment corridors and scenario-based planning. Ethiopia’s Home-grown Economic Reform Plan emphasized macro-fiscal stability and export competitiveness as levers for growth. In each case, ambition was supported by structural scaffolding.

Tanzania’s Dira, in contrast, appears more aspirational than operational. Without embedded delivery systems, budget realism, and institutional coordination, its six pillars may remain noble declarations rather than engines of transformation. Turning vision into outcomes will require stronger connective tissue—especially between national planning and real-world constraints.

This brings us to a more immediate and practical challenge: the design of FYDP IV (2026–2030), the first five-year development plan under the Dira. Tanzania’s past plans have had mixed results. FYDP I (2011–2015) emphasized infrastructure but struggled with execution delays and underfunding. FYDP II (2016–2020) focused on industrialization and human development but underperformed in export diversification. FYDP III (2021–2025) introduced competitiveness and digital inclusion but has faced persistent bottlenecks in coordination and budget discipline.

If FYDP IV is to mark a genuine shift, it must be structured differently. First, it should anchor targets in fiscal realism, ensuring that ambitions match available resources and absorptive capacity. Next, it should adopt scenario-based economic modelling to account for volatility in commodity prices, demographic shifts, and global headwinds. Third, rather than listing broad aspirations, the plan must sequence a few catalytic priorities—those with high multiplier effects across sectors. These might include agro-processing value chains, rural electrification, and digital education reform.

Perhaps most importantly, FYDP IV should embed a delivery mechanism: a national performance unit or delivery lab to track key performance indicators, troubleshoot implementation delays, and issue regular progress reports. Such an approach would provide real-time feedback, enabling government to adapt and course-correct as needed. This kind of adaptive governance—based on learning and iteration—is what turns planning into problem-solving.

The upcoming five-year plan also presents an opportunity to institutionalize external accountability mechanisms. This includes stronger roles for Parliament, civil society, and independent researchers to assess whether progress aligns with stated objectives. Open budget data, citizen feedback loops, and performance dashboards should become routine, not exceptions.

If Tanzania fails to address these issues in FYDP IV, the Dira may fall into the same trap as many long-term visions: ambitious on paper, elusive in practice. But if the five-year plan becomes a disciplined, realistic, and accountable bridge to 2050, the country could lay a credible foundation for sustainable transformation.

Ultimately, Tanzania’s USD 7,000 ambition is not simply an economic target—it’s a test of national coordination, courage, and competence. While the numbers may appear daunting, they are not unattainable if backed by institutional alignment, fiscal discipline, and smart prioritization. The Dira has given the nation a direction. The task now is to build the road.

The first stretch of that road begins with FYDP IV. If the next five years are used not as a warm-up, but as a take-off, Tanzania may move from vision to velocity. But if they are approached with business-as-usual thinking, the gap between dreaming and doing may only widen. The moment calls for more than a plan—it calls for a delivery revolution.

100510 956097I dugg some of you post as I thought they were really useful handy 822307