How SADC nations are navigating the road to 2030

AS the 2030 deadline for the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) approaches, the Southern African Development Community (SADC) has made significant progress toward achieving SDG 4 ensuring inclusive and equitable quality education for all.

However, despite this progress, the region still faces major challenges that hinder the full realization of this goal. SADC is a regional bloc of 16 countries with diverse socio-economic conditions, from upper-middle-income nations like South Africa and Botswana to low-income countries such as Malawi and Mozambique.

Education is a key focus of SADC’s Regional Indicative Strategic Development Plan (RISDP), which aligns with SDG 4’s objectives, including universal access to education, vocational training, and higher education.

These initiatives aim to build human capital, reduce inequality, and promote sustainable development across the region.

On the Day of the African Child this year, SADC Parliamentary Forum Secretary General, Boemo Sekgoma, highlighted that millions of children in the region still lack inclusive and quality education due to factors such as child marriage, early pregnancies leading to school dropouts, gender discrimination favoring boys’ education, child labor, and displacement due to climate disasters.

She stressed that every child in Africa should have the opportunity to realize their dreams through education, which requires collaboration from both state and non-state actors to create a world of equal opportunities.

Regional achievements

Over the past two decades, SADC member states have made notable improvements in school enrollment and education quality. For example, primary education completion in Africa increased from 52% to 69%, lower secondary from 35% to 50%, and upper secondary from 23% to 33% between 2000 and 2023.

However, significant gaps remain. The World Bank estimates that over 46 million children in Eastern and Southern Africa remain out of school, particularly those affected by conflict, climate emergencies, and disabilities.

Human Rights Watch notes that these vulnerable groups face additional risks such as child marriage, labor exploitation, and recruitment into armed groups.

In Tanzania and other parts of the region, where child marriage is still prevalent, activists, including Rebeca Gyumi, Executive Director of the Msichana Initiative, are calling for the amendment of the 1971 Marriage Act, arguing that the law undermines the dignity and future prospects of children and girls in Tanzania. Countries like Tanzania and Namibia have achieved near-universal primary school enrollment.

Tanzania, for example, abolished primary school fees, leading to a significant increase in attendance. Similarly, eight countries, including Zimbabwe and Eswatini, have achieved 75% coverage for early childhood development indicators.

Zimbabwe’s Early Childhood Development (ECD) program has driven higher enrollment in pre-primary education. South Africa, Tanzania, and Namibia have also expanded access to technical and vocational education and training (TVET), addressing skills gaps and rising unemployment.

These countries have also made strides in improving school infrastructure, ensuring that most schools have access to clean water and electricity. In addition to regional efforts, countries outside SADC have also set valuable examples. Kenya’s Tusome program, for instance, has significantly improved Kiswahili reading levels among first and second-grade students.

In the Democratic Republic of Congo, the elimination of primary school fees in 2019 resulted in a 25% increase in primary school enrollment, benefiting 3.7 million additional children. Persistent Challenges Despite these positive developments, significant challenges remain.

Vulnerable groups, including rural children, those with disabilities, and refugees, continue to face barriers to education.

In Mozambique, for instance, the Ministry of Education and Human Development failed to provide essential teaching materials this year, such as free school textbooks, which are prohibited from being sold.

In the Democratic Republic of Congo, the UNHCR struggles to ensure refugees have access to education. Even for those enrolled in school, quality remains a major concern.

Nine out of ten children in sub-Saharan Africa cannot read and understand a simple story by age 10. According to the World Bank’s latest report, Ending Learning Poverty: What Will It Take?, without substantial action, 89% of children completing primary school by 2030 will remain “learning poor.”

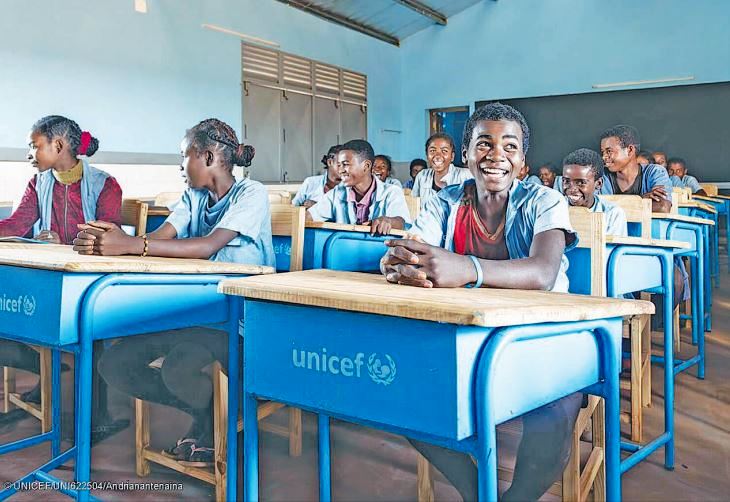

Different countries in SADC have adopted varying approaches to address these challenges. Namibia, for example, has improved its Education Management Information System (EMIS) in collaboration with UNICEF, providing reliable data on enrollment and teacher qualifications.

However, gaps remain in tracking literacy, especially among younger learners. Zimbabwe has implemented a web-based EMIS that improves data accuracy, although challenges persist in tracking dropout rates, particularly among socio-economically disadvantaged groups.

Mozambique has seen progress in pre-primary education enrollment but struggles with high dropout rates and insufficient data on learning outcomes in rural areas.

Tanzania has committed to tripling its annual TVET enrollment to 1.5 million by 2030 and incentivizing innovation in key sectors like digital technologies and green skills.

ALSO READ: Fed’s gamble: A cut that stirs chaos and uncertainty

The country’s Prime Minister, Kassim Majaliwa, announced that 25 new Vocational Training (VETA) colleges have been completed, with an additional 65 under construction.

SADC countries like Seychelles and Mauritius report literacy rates above 90% for both men and women, while Namibia has achieved near gender parity.

In contrast, countries like Mozambique and Malawi have lower literacy rates, particularly for females. In Mozambique, as of 2024, the overall adult literacy rate is 58.55%, with a significant gender gap. Male adults have a literacy rate of 73.26%, while female adults have a much lower rate of 45.37%.

Among youth, the literacy rate is 76.67%, with 83.67% for males and 69.73% for females, emphasizing the need for targeted efforts to close the gender gap in education.

This year, the African Union declared 2024 the “Year of Education,” focusing on “Building Resilient Education Systems for Increased Access to Inclusive, Lifelong, Quality, and Relevant Learning in Africa.”

According to Lieke Van Der Wiel from UNICEF, this initiative presents an opportunity to improve education across the continent and develop human capital for Africa’s future.

The spotlight

Despite progress, substantial investment is needed to meet SDG 4 targets. UNESCO estimates that achieving universal education in the region will require an additional 9 million classrooms and 9.5 million teachers by 2060.

This highlights the need for efficient resource use, innovative public-private partnerships, and international support.

Activists and education stakeholders argue that priority should be given to the most vulnerable groups, including children with disabilities, rural populations, and those affected by conflict.

South African education activist Poliwe Lolwana suggests that education should extend beyond traditional classrooms, utilizing community centers and other unconventional spaces as learning hubs.

SADC reports show that the bloc has made efforts to address educational challenges through initiatives like the Southern African Power Pool, which aims to ensure reliable electricity for schools.

Shared teacher training programs and collaborations with organizations like UNESCO and UNICEF provide technical and financial support for education reforms. Scaling these efforts is crucial to mitigate the impact of displacement, conflict, and climate emergencies on education.

To accelerate progress toward SDG 4, researchers Marcina Singh and Tabitha Mukeredzi recommend that SADC member states focus on strengthening their Education Management Information Systems (EMIS) to fill data gaps, particularly in literacy and vocational skills.

Aligning national education systems with international standards, targeting funding to underserved areas, and developing inclusive policies for marginalized groups will be essential.

They also emphasize investments in teacher recruitment, professional development, and integrating disaster preparedness into education planning.

Building climate-resilient infrastructure and fostering cross-border knowledgesharing are key to ensuring long-term educational progress.

As Singh and Mukeredzi note, “The positive effects of good-quality teachers cannot be overstated.” Teachers not only improve education systems but, as agents of citizenship and social cohesion, they shape the actions and beliefs of learners as they become active citizens in society.

Looking ahead

While SADC has made important strides in addressing educational challenges, significant barriers remain.

The region’s diverse socioeconomic conditions and disruptions like the COVID-19 pandemic continue to impact educational progress.

Education experts and organizations like UNESCO and UNICEF are calling for urgent action to overcome these obstacles and ensure quality education for all children in the region. The path to 2030 for SADC nations to achieve SDG 4 is complex, with both opportunities and challenges.

While substantial progress has been made in expanding access to education, more work is needed to improve education quality and ensure no child is left behind.

As 2030 approaches, a collective commitment to strengthening education systems, fostering collaboration, and prioritizing inclusivity will be crucial.

Education lays the foundation for sustainable development, and energy is the driving force powering progress. In the next part of our series, we will explore how SADC nations are navigating the clean energy transition.