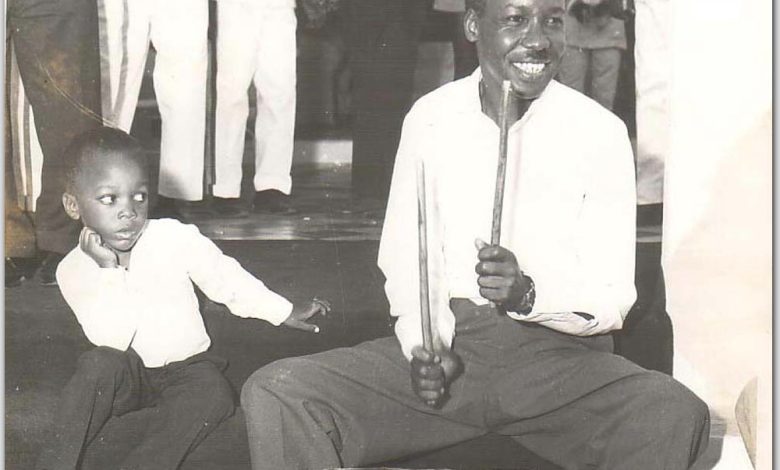

From childhood Mwalimu had all signs of a leader

MARA: MENTION the name Mwalimu Julius Kambarage Nyerere anywhere in Tanzania or beyond and attention immediately shifts.

All eyes would turn toward the son of a Zanaki chief from Butiama, in Mara Region, formerly part of the British colony of Tanganyika.

Born in a humble village but destined for greatness, Mwalimu Nyerere would go on to become the founding father of Tanzania and one of Africa’s most revered leaders.

As the country commemorates the 26th anniversary of his death, the question arises: How did this soft-spoken teacher from a remote village become not just the President of Tanganyika, but also co-founder of the United Republic of Tanzania alongside Zanzibar’s Abeid Amani Karume? Julius Nyerere was born on April 13, 1922, in Mwitongo, a small area in the village of Butiama, not far from Musoma town.

His full name that is Julius Kambarage Nyerere reflected his Zanaki heritage and he was one of 25 surviving children of Burito Nyerere, a local chief.

Though he was born into a relatively privileged family by village standards, his early life was anything but lavish.

Like many boys of his time, young Julius assisted in farming chores growing millet, maize and cassava and helped herd goats and cattle.

According to Wandibha Magesa, a fellow Zanaki elder now in his eighties, the signs of future greatness in Nyerere were apparent even in childhood.

“A chicken that will become a cock can be spotted the day it hatches,” he said, using a local proverb.

The name “Nyerere” in Zanaki translates to “caterpillar” a name symbolising endurance and transformation. According to elders, the caterpillar represented the hardship and resilience the community endured, and perhaps, fore shad owed Julius Nyerere’s own path.

Education and early exposure to power Despite traditional expectations, Nyerere underwent Zanaki initiation rituals, including circumcision at Gabizuryo, in keeping with local customs. However, his path soon took a different turn.

The British colonial administration, hoping to co-opt local leadership and prevent the rise of an educated elite that could challenge their rule, encouraged Chief Burito to send his son to school.

In 1934, Nyerere began formal education at the Native Administration School in Mwisenge, Musoma, where lessons were conducted in Kiswahili as a language he had to learn, as he grew up speaking Kizanaki.

He quickly rose through the academic ranks, attending Tabora Secondary School, and later, Makerere University in Uganda, from 1949 to 1952, where he studied alongside some of East Africa’s brightest minds.

Eventually, Nyerere moved to the University of Edinburgh in Scotland, becoming the first Tanganyikan to study in the United Kingdom. It was during this period that his political consciousness matured.

Inspired by global anti-colonial movements and ideas of social justice, he returned home determined to help his people gain independence.

Upon his return to Tanganyika, Nyerere began teaching but quickly realised that political action was essential. In 1953, he joined the Tanganyika African Association (TAA), becoming its president.

A year later, he transformed it into a political movement—the Tanganyika African National Union (TANU).

Under his leadership, TANU advocated for peaceful change, racial harmony, social equality, and a complete rejection of tribalism and racial discrimination. His charisma and vision united diverse ethnic groups under one national identity.

Two years ago, according to Charles Atesh, a local historian and former member of the Tanzania Family Peace Promoters Society, Nyerere was more than just a political leader, he was a humanist.

“He had a vision that few people could understand at the time. He despised tribalism and believed deeply in national unity,” Atesh said.

Nyerere promoted Kiswahili as the national language, encouraged inter-ethnic marriages and urged citizens to see themselves first and foremost as Tanzanians, not as members of separate tribes.

He once wondered aloud, with his characteristic humour, how anyone in their right mind could discriminate against an- other simply based on tribal background in jobs or education.

His efforts were not limited to Tanganyika. Nyerere played a crucial role in the formation of the Organisation of African Unity (OAU) now the African Union (AU).

He strongly believed that Africa’s liberation was incomplete until all its people were free, particularly those in Southern and Eastern Africa still under colonial or minority rule.

When Tanganyika transitioned from a British League of Nations mandate to a UN Trusteeship, independence became inevitable.

Nyerere sought to accelerate this process, using TANU as his po- litical vehicle. On December 9, 1961, Tanganyika gained independence, with Nyerere as Prime Minister, and later President.

ALSO READ: Nyerere, a leader in the making from childhood

Following the 1964 revolution in Zanzibar, Nyerere worked closely with President Karume to unite the two nations, forming the United Republic of Tanzania—a rare and enduring example of a peaceful African union.

Tanzania’s diplomatic influence also grew, largely thanks to Nyerere’s principled stance on African liberation and his support for countries such as Uganda, Mozambique, Zimbabwe, and South Africa during their struggles for independence.

Mwalimu Nyerere “Mwalimu” meaning teacher in Kiswahili was deeply committed to education, equity and self reliance.

He declared war on poverty, disease, and ignorance, famously stating: “Poverty, ignorance and disease are not mock enemies. They are the true enemies of our people. And anybody who refuses to take part in this war, or who hinders the efforts of his neighbours, is guilty of helping a far more deadly foe than is he who helps an armed invader.”

His policies under the Ujamaa (African socialism) philosophy aimed to build a just and egalitarian society.

Although Ujamaa faced economic challenges, it succeeded in promoting national unity and eradicating tribalism—two of Nyerere’s core priorities.

His son, Charles Makongoro Nyerere, fondly remembers him as “Mzee Kifimbo,” a nickname referring to the small baton he often carried— his signature symbol, much like Kaunda’s white handkerchief or Kenyatta’s fly-whisk.

“My father will always be remembered for uniting Tanzanians and promoting hard work and self-reliance,” said Makongoro.

“He loved this nation with all his heart.” Nyerere voluntarily stepped down from power in 1985, a rare act in African politics at the time.

Yet, even in retirement, he continued to serve Africa, playing a key role in the Burundi peace negotiations and advocating for social justice and African unity. Under his leadership, Tanzania emerged as a respected voice in global affairs.

His push for equitable relations between the Global South and North, his moral authority, and his unwavering integrity won him admirers around the world. His legacy was not just in policies, but in character.

He governed with humility, re- fused to accumulate wealth, and remained committed to serving people until his last breath.

Remembering Mwalimu

Mwalimu Julius Nyerere passed away on October 14, 1999, at the age of 77. But his ideals freedom, unity, justice, and self-reliance live on.

His slogan, “Uhuru na Umoja” (Freedom and Unity), still resonates today. The peace and stability that Tanzania en- joys, the strength of its national identity, and its role as a diplomatic hub in East Africa all stem from the foundation Nyerere laid.

He remains a source of inspiration not just for Tanzanians, but for all Africans striving for dignity, unity, and genuine independence.

So today, as we reflect on 26 years since his passing, let us not only celebrate his life, but live by his principles.

Let us remember Mwalimu Julius Nyerere not only as the father of the nation but as Africa’s teacher, philosopher, lib- erator, and conscience. Rest in peace, Mwalimu. Your wisdom guides us still.