COLUMN: THE CLIFF. Hormuz fire: Africa’s budgets burn next?

THE Strait of Hormuz, a critical global oil passage, often seems a distant concern for African economies. Yet, as geopolitical tensions simmer in the Middle East, their ripple effects threaten a fiscal firestorm across Africa, potentially pushing national budgets to their breaking point.

This isn’t hypothetical; converging forces of global energy volatility, escalating debt, inflation, and soaring borrowing costs are visibly evident, demanding urgent attention from policymakers.

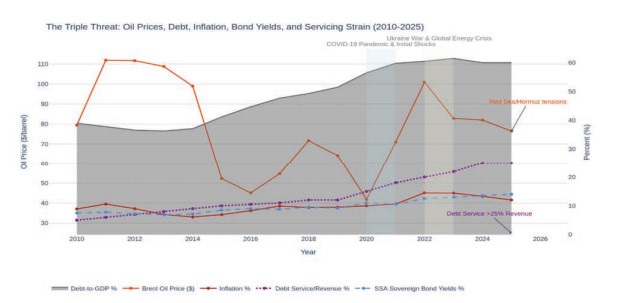

A comprehensive look at key macroeconomic indicators for Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) over the last decade and a half reveals a perilous trend as illustrated in the accompanying chart. Global Brent Crude Oil Price, a direct igniter of economic volatility, highlights Africa’s immediate exposure. Prices surged over USD 100 per barrel in 2011-2012 and again in 2022.

More acutely, the current situation in the Red Sea, marked by active attacks on commercial shipping, forces tangible rerouting of vessels around the Cape of Good Hope. This on-the-ground disruption significantly increases shipping costs, extends travel times, and inflates insurance premiums, directly raising import costs and fuelling inflation across Africa.

Whilst higher oil prices might offer a temporary revenue boost for SSA’s oil-exporting nations, their fiscal benefits are often quickly offset by increased costs of other imported goods, global inflationary pressures, and the broader instability.

Adding to this volatility, the Strait of Hormuz, though not under direct assault, remains central to the ‘tensions’ narrative due to the elevated geopolitical risk stemming from the ongoing full-blown war between Iran and Israel and its wider regional impact.

Any escalation in this vital energy chokepoint would catastrophically disrupt global oil supplies, magnifying the risk already posed by the Red Sea situation to African nations already grappling with limited buffers.

ALSO READ: UNDP-supported climate change project yields result in TFS Southern Zone

This external volatility consistently mirrors the internal SSA Inflation Rate, which spiked to 14.5 per cent in 2022 and remained elevated at 14.4 per cent in 2023. Such inflation erodes purchasing power, increases living costs, and pushes governments to spend more on subsidies, further straining tight budgets.

This external pressure is compounded by an alarming internal dynamic: deepening public debt. The average SSA Public Debt-to-GDP ratio has shown relentless expansion, swelling from approximately 39.0 per cent in 2010 to surpass 60 per cent by 2023, a critical threshold signalling heightened risk and shrinking fiscal space.

This debt accumulation, notably accelerating during the 2020-2021 COVID-19 pandemic and initial shocks, leaves less room for essential investment or effective crisis response. The direct consequence is captured by the SSA Debt Service to Revenue Ratio, which surged from around 5.0 per cent in 2010 to an alarming 21.9 per cent in 2023, projected to exceed 25 per cent by 2025.

This means over a quarter of national revenue could soon be consumed by debt repayments, diverting critical funds from healthcare, education, and infrastructure. Adding another perilous layer is the escalating cost of borrowing.

Average SSA Sovereign Bond Yields, a manageable 7.5 per cent in 2010, have shown a concerning upward trajectory. After remaining relatively stable between 7-9 per cent until 2018, yields sharply increased to 11.0 per cent in 2020 and surged further to 12.5 per cent in 2022 and 13.0 per cent in 2023, with projections placing them at 14.0 per cent by 2025.

This steep rise directly impacts national budgets, as new borrowing or refinancing comes at significantly higher interest rates. Such escalating costs, a clear indicator of financial markets’ increased risk perception, trap countries in a cycle where an ever-larger share of revenue must be allocated to servicing obligations, rather than fostering growth or building resilience. The human cost of these macroeconomic pressures is profound.

As national budgets are squeezed by external shocks and mounting debt obligations, the ripple effects are felt directly by citizens. Higher inflation means essential goods like food and fuel become unaffordable, eroding household purchasing power. Concurrently, diversion of government revenue towards debt servicing inevitably reduces public spending on vital social services, hampering long-term development and exacerbating poverty.

Moreover, foreign exchange reserves, needed to cushion against shocks, are under immense pressure, dwindling as countries battle rising import bills and capital flight, further diminishing their capacity to respond effectively.

This grim outlook for African sovereign borrowing is further exacerbated by recent decisions from major global central banks. After aggressive interest rate hikes, many, including the U.S. Federal Reserve, have signalled a pause on rate cuts, or even hinted at further hikes if inflationary pressures persist.

ALSO READ: Tanzania livestock vaccine factory draws continental praise

This cautious stance stems from inflation proving stickier than anticipated and resilient labor markets in developed economies.

For African nations, this means the era of cheap global money is over; borrowing costs are likely to remain elevated. A stronger USD, often a consequence of higher interest rates, simultaneously makes USD-denominated debt more expensive to service locally and critical imports even pricier.

Navigating this treacherous economic landscape demands proactive and multifaceted strategies. African governments must intensify domestic revenue mobilisation, broadening tax bases and curbing illicit financial flows. Prudent debt management is paramount, involving transparent borrowing, exploring debt restructuring, and prioritising concessional financing.

Furthermore, economic diversification away from volatile commodities, coupled with investments in value addition, manufacturing, and technology, is crucial for building long-term resilience. Building adequate fiscal and foreign exchange buffers during calm periods remains imperative.

This domestic resolve must also be met with strengthened international cooperation, advocating for a fairer global financial architecture that provides more equitable access to finance and support for climate resilience, without which the continent’s efforts to avert fiscal disaster could prove insufficient.

The confluence of these trends paints a stark picture: African budgets are under immense, multifaceted pressure. Rising global oil prices and persistent inflation continue to erode purchasing power and drain foreign exchange, while an expanding debt burden is coupled with increasingly expensive debt servicing and higher borrowing rates in a sustained high-interest global environment.

The lessons from past shocks are clear: external crises disproportionately impact economies with limited buffers. As the world watches tensions, African leaders must recognise their budgets are on the frontline. The fiscal fire is already smouldering; without urgent and coordinated action, the next global shock could indeed see Africa’s budgets burn, with devastating consequences.

As the 19th-century American philosopher Ralph Waldo Emerson wisely observed, “Cause and effect, means and ends, seed and fruit, cannot be severed; for the effect already blooms in the cause, the end preexists in the means, the fruit in the seed.” The seeds of Africa’s next fiscal crisis are being sown by global events and domestic vulnerabilities, and the continent must prepare for the harvest.