Breast cancer: New study finds genetic risk in African women, look at what should be done

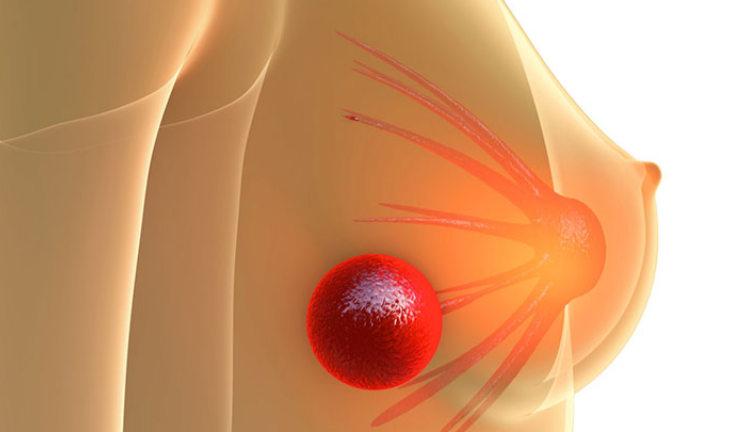

AFRICA: BREAST cancer is the most common cancer in women worldwide. In sub-Saharan Africa, it is a leading cause of cancer-related deaths among women.

Risk factors for developing breast cancer include being female, increasing age, being overweight, alcohol consumption and genetic factors.

In this field, genomewide association studies are a powerful tool. They can identify common genetic variants, or mutations, that can affect your likelihood of developing a trait or disease. These studies scan the whole genome (all of a person’s DNA) to find genetic differences present in people with a particular disease or traits.

Since their introduction in 2005, these studies have provided insights that can help in the diagnosis, screening and prediction of certain diseases, including breast cancer. Recent findings have been used to develop prediction tools that help identify individuals at high risk of developing diseases.

Genetic risk scores (also known as polygenic risk scores) estimate disease predisposition based on the cumulative effect of multiple genetic variants or mutations.

But most research has been conducted on populations of European ancestry. This poses a problem, as genetic diversity and environmental variability differ across the world. In Africa, even greater genetic diversity is observed across populations.

To fill this gap we – researchers from Wits University, Sydney Brenner Institute for Molecular Bioscience, and our collaborators, the South African National Cancer Registry – conducted the first genome-wide association study of breast cancer in a sub-Saharan African population.

We compared genetic variation between women with breast cancer and those without, looking for variants that occur more frequently in the cancer patients.

We identified two genomic variants close to the RAB27A and USP22 genes that contribute to the risk of breast cancer in South African black women. These genetic variants have not been previously found to be associated with breast cancer in non-African populations.

Our findings underscore the importance of identifying population-specific genetic variants, particularly in understudied populations. Different populations may carry unique variants that contribute differently to breast cancer risk. Risk variants found in other populations might not be found in African populations. This reinforces the idea that research efforts and risk scores must be done in different populations, including African ones.

Comparing women’s DNA

DNA samples from 2,485 women with breast cancer were compared to 1,101 women without breast cancer. All the women were residents of Soweto in South Africa. The breast cancer cases were recruited to the Johannesburg Cancer Study over 20 years and the controls were from the Africa Wits-INDEPTH Partnership for Genomic Research study.

The analysis used technology (called a DNA chip) specially designed by the H3Africa consortium to capture the genetic variants within African populations.

By comparing genetic variation in women with breast cancer and in those without, we identified two genetic variants that contribute to the risk of breast cancer in South African black women. They occur around genes that are involved in the growth of breast cancer cells, in the ability of cancer cells to metastasise (spread), and in tumour growth in different cancers.

We also applied polygenic risk scores to our African dataset. This is a method that estimates the risk of breast cancer for an individual based on the presence of risk variants. These are derived from the results of genome-wide association studies. The risk score we used was based on risk variants from a European population. We used it to evaluate its ability to predict breast cancer in our African population.

The results showed that the risk score was less able to predict breast cancer in our sub-Saharan African population compared to a European population.

What next?

This is the first large-scale genome-wide association analysis in sub-Saharan Africa to find genetic factors that affect an individual’s risk of developing breast cancer.

Our study included fewer than 4,000 samples. Larger breast cancer genetic studies have involved over 200,000 cases and controls, but without representation from subSaharan African populations. This highlights the urgent need for greater research efforts and increased participation from the continent.

The results from this and future studies will help doctors screen patients and pinpoint those with a high risk. Once we know who is at high risk, they can be offered more frequent check-ups and preventive measures. This allows us to catch breast cancer early – or even prevent it – before it has a chance to develop or spread.

Further research will be needed to understand how these genes increase the risk of developing breast cancer and improve breast cancer prediction. Notably, applying European-derived polygenic risk scores did not accurately predict breast cancer in the African dataset. And they performed worse than in non-African datasets. These results are consistent with findings reported previously for other diseases.

We are involved in a global study of the genetics of breast cancer called Confluence which is looking at genetic risk factors in many populations, including African ones.

Every year breast cancer claims more than 650,000 lives worldwide.

Survival rates have been recorded to be as high as 90% in high income countries. In sub-Saharan Africa the rate is less than 40 per cent.

A recent study found that the incidences of breast cancer in sub-Saharan Africa had increased by 247% from 1990 to 2019. The highest incidence was recorded in Nigeria.

For Breast Cancer Awareness Month we highlight four essential reads about the difficulties women in Africa must overcome to survive this cancer.

Catching it early

People living in low- and middle-income countries, such as Nigeria, are highly vulnerable to breast cancer. Surgeon and lecturer Olalekan Olasehinde explains that this is mainly because people in these countries seek medical help at a late stage when the disease is advanced. When breast cancer is at an advanced stage, it is harder to treat and people are more likely to die.

Olasehinde outlines the five things one can do to detect breast cancer early and reduce the risk of death. The signs to look for include lumps in the breast and changes in the size or shape of the breast