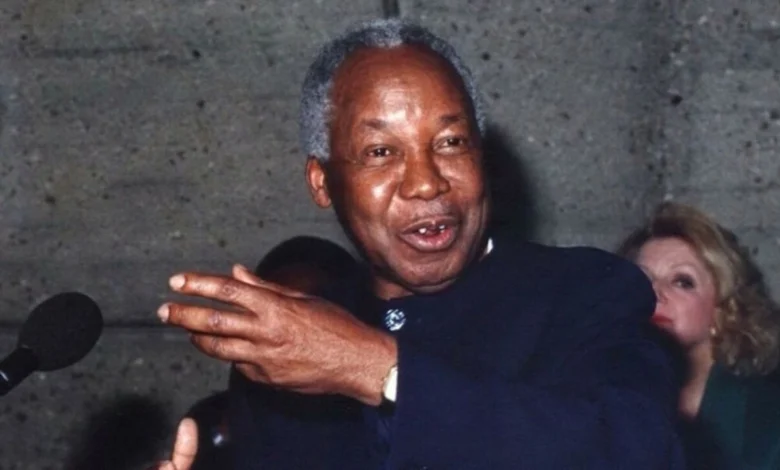

Mwalimu Nyerere: Education reformist who fought ignorance

TANZANIA: IMAGINE taking over the leadership of a nation with only 11 graduates while the county’s population stands at 9 million people.

It is something inconceivable. When Tanzania (Tanganyika) gained her independence on December 9, 1961, after years of colonialism, first under Germany and later Britain, the country had only 11 indigenous university graduates.

Records show that 71 per cent of the senior civil service were expatriates and the level of illiteracy among the Tanzania population was at its highest level.

Some revisited documents state that at independence in 1961, the illiteracy rate was 77 per cent while others say it was over 80 per cent.

Tanzania found itself in this situation after independence because in the pre-colonial period, informal education was the norm, with knowledge and skills passed down from one generation to the next.

The German colonial regime introduced formal education, focusing on training bureaucrats for adminis- trative roles. This included training in Swahili and basic administrative skills.

During the British colonial pe- riod the emphasis shifted towards a broader educational agenda. It (Brit- ish rule) recommended adapting education to local needs, particularly in agriculture.

After independence, Founding Mwalimu Julius Nyerere was indeed conscious that, he could not succeed in eradicating ignorance, disease and poverty, a campaign he had proclaimed, branding them as the three enemies of the nation.

Hunger, widespread disease and low average life expectancy of just above 40 years, were also major obstacles to development.

He was also aware that adults, the majority of whom were peasants, livestock keepers and fisher- men, had to be reasonably equipped with reading, writing and numeracy skills, to be able to function beneficially and intelligently.

That being the case, Mwalimu Nyerere, himself a focused teacher, devised some strategies to fight illiteracy among the Tanzania population. The first strategy that was rolled out was the implementation of adult education.

People who helped to implement this campaign include volunteer primary school pupils who offered part of their spare time to instruct their elders, policy over- seers and coordinators.

The campaign was implemented at the lightning speed such that but by 1967, illiteracy had been reduced to 69 per cent; and by the mid-1980s, the figure had dropped to less than 10 per cent.

Experts in educational philosophy like Prof Abel Ishumi from the University of Dar es Salaam say the object of adult education in Tanzania was not merely to teach literacy, but to help adults find solutions to other problems such as hunger, ignorance, disease and soil erosion.

Adult education was seen as vital to the spread and implementation of Ujamaa or African Socialism in the countryside.

The experts say Nyerere’s philosophy on adult education, lifelong learning and education for liberation was in many ways a natural development of his ideas embodied in Education for Self-Reliance, particularly those relating to some of the inherent limitations and inadequacies of formal schooling.

They say that Nyerere’s conviction about the role of adult education as a means of development and as a part of development has been recognised by many development planners, economists and educators.

In addition to imparting knowledge and skills, he looked on adult education as basically a political process.

According to Nyerere, one of the primary and most significant functions of adult education was to arouse consciousness and critical awareness among the people about the need for and possibility of change.

The second function or stage of adult education was to help people to determine the nature of the change they wanted and how to bring it about.

But, according to Mzee Pius Msekwa, the first CCM Secretary General (Executive Secretary), Mwalimu Nyerere’s resolve to fight ignorance and reform education started with his vision on ‘education for self-reliance.’

He says education for self-reli- ance was first given expression in the TANU’s policy document titled: “The Arusha Declaration on Social- ism and Self-reliance,” which was promulgated on 5th February, 1967.

“This was during the first de- cade of the country’s independence, which was characterised as the ‘period of vibrancy’ in terms of ‘resolution, action and bold attempts at innovation,”

ALSO READ: FORMER LEADERS’ BENCH WITH DAILY NEWS: Revered strategist, reformist

Mzee Msekwa says in one of his write-ups titled ‘Memories of Mwalimu Nyerere; His Vi- sion on Education and Self-reliance.’

According to Mzee Msekwa, Mwalimu Nyerere himself found time to write and publish a book in which he said: “Our education must inculcate a sense of commitment to the total community, and help the students to accept the values that are appropriate to our future, and not to our colonial past.”

By that Mwalimu meant that the country’s education had to be consistent with and complementary to, the ambitions of a society aspiring to a socialist mode of existence, characterised by respect for human dignity, equality, participation in cooperative endeavours and, above all, commitment to hard, productive work.

Quoting Mwalimu Nyerere’s words, Mzee Msekwa says, “Our schools must become communities that actually practice the precept of self-reliance.

The teachers, the other school workers and the students, must be members of a social unit in the same way as the members of an Ujamaa village are expected to be, namely, a social unit consisting of people who live together and work together, for the benefit of all.”

The former National Assembly Speaker and University of Dar es Salaam Vice Chancellor share more insights, saying the government’s Three-Year Development Plan (1961 – 4), which was put in place immediately after the attainment of the country’s independence, recorded no less than six practical decisions affecting the education sector alone.

They included racial integration of the school system; the rapid expansion of secondary education by establishing more schools, increasing student enrolment; the expansion of teacher teaching programmes and the termination of parent payable school fees; among others.

“These were Mwalimu Nyerere’s initial tasks after the achievement of independence; which entered primarily on building a new country which is distinctly different from that which we inherited from the colonialist,” Mzee Msekwa points out.

But academicians such as Gloria Mbogoma state that being an educator and a Head of State, Mwalimu Julius questioned the rationale of the education system inherited from colonialism which perpetuated exploitation and underdevelopment in post-colonial Tanzania.

She says the late Mwalimu Nyerere noticed that the education system, after the country gained her political independence in 1961, did not sufficiently meet the needs and social objectives of Tanzanians.

According to Mwalimu Nyerere, colonial education was offered to a few individuals to meet the objectives of the coloniser.

He therefore proposed that schools must not only become integral parts of the community and society but also carry out activities designed to make them financially self-sufficient.

This missing link is what prompted Mwalimu Nyerere to come up with an Education for Self-Reliance policy with the goal of re-examining and modifying the education system so that it could meet the objectives of Arusha Declaration which was formulated in 1967.

“Education for Self-reliance emerged as an attempt to revolutionise the educational system, making it more relevant to Tanzanians, while using education as a vehicle for eliminating socioeconomic inequalities in Tanzania and cultivating a culture of self-reliance,” says Ms Mbogoma in her paper for the Master Degree submitted to the University of Pretoria.

Prof Derek Mulenga from University of South Florida says Mwalimu Nyerere introduced Universal Primary Education (UPE) programme in 197Os in keeping with its “education for self-reliance” policy.

Implementation of Ujamaa Village programme also enabled the government to increase schools and other infrastructures for social service provision. Provision of education was also guaranteed in the constitution as a basic human right.

Under UPE programme each child aged seven years was obliged to go to school to acquire education that was provided freely.

Massive enrolment of children into schools necessitated Mwalimu Nyerere to come up with a strategy of preparing teachers to bridge the gap that emerged.