Tanzania at Crossroads with Japan and Singapore

DAR ES SALAAM: In August 2025, two summits just days apart—the Tokyo International Conference on African Development (TICAD9) in Yokohama and the Africa–Singapore Business Forum (ASBF) in Singapore—set clear markers for Asia’s engagement with Africa.

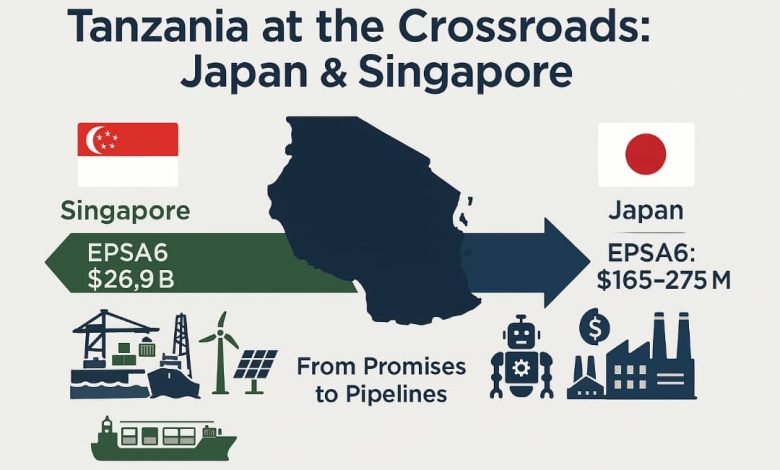

TICAD9 ended with the Yokohama Declaration to “co-create innovative solutions with Africa,” anchored by USD 5.5 billion in new support for the private sector under EPSA and a pledge to train 30,000 AI specialists, while ASBF highlighted Singapore–Africa ties with trade rising over 50 percent from SGD 12.1 billion in 2020 to SGD 18.7 billion in 2024, investments exceeding SGD 26.9 billion by end-2023, and new Bilateral Investment Treaties with Côte d’Ivoire and Nigeria.

Together these outcomes move the conversation from promises to pipelines, sharpened by Africa’s annual infrastructure financing gap of USD 130–170 billion and its USD 200 billion energy and climate investment needs by 2030.

Yet Japan–Africa trade remains modest at about USD 8.7 billion in exports and USD 9.1 billion in imports in 2024, compared with China–Africa flows in the hundreds of billions.

The implication is clear: Japan brings terms and technology, Singapore brings capital, logistics, and rules, and Tanzania’s task is to position itself to capture both.

Tanzania’s positioning must begin at home, where trade data already reveal the scale of opportunity: in 2023 the country imported USD 649 million from Japan and USD 157 million from Singapore, yet exports to both markets remain less than USD 70 million per country thus underscoring a clear gap to close.

To address this imbalance, the post-election administration can translate summit opportunities into law and policy that are concrete, time-bound, and fiscally disciplined.

A National Asia–Tanzania Partnership Strategy issued within the first 100 days should mandate the PPP Centre to publish a rolling, bankable project pipeline—covering ports and intermodal nodes on the Central and Mtwara corridors, renewable and grid reinforcement investments, and agro-processing parks—screened against cash-flow and environmental criteria before submission to JBIC, JICA, and Singaporean investors.

ALSO READ: Tanzania edges toward trade, industry recovery

Anchored in Tanzania’s Investment Act (2022/23) and the updated PPP framework (2023 amendments and 2024–25 guidance), which already streamline entry, clarify viability-gap funding, and shorten approvals, such a pipeline would shift Tanzania from reactive deal-making to proactive strategy.

With tested projects in place, the country could credibly target 3–5 percent of EPSA6 disbursements over 2026–28—USD 165–275 million annually—rather than relying on ad-hoc arrangements.

Financing must then be structured to protect the balance sheet.

The Bank of Tanzania and the Treasury can codify a Blended Finance Policy that pairs Japanese concessional loans (some recent EPSA tranches have featured very low interest and 40-year maturities) with equity/mezzanine from Singapore funds and local-currency tranches from TDB or pension funds, while layering JBIC/AfDB guarantees.

The aim is explicit: cap FX-denominated debt at ≤40 percent of project capital and reduce average cost of capital by 200–400 bps versus pure commercial borrowing—a necessary discipline given IMF program documents showing elevated debt service–to-revenue ratios in FY2023/24–2024/25.

These numerical caps can be written into PPP approvals to ensure bankability without destabilizing debt dynamics.

Investor certainty is the third leg. A fast-track Bilateral Investment and Standards Acceleration Bill should authorize the government to conclude and ratify BITs and DTAs with Japan and Singapore on a defined timetable, mirroring the ASBF model that saw the Côte d’Ivoire and Nigeria BITs enter into force.

In parallel, regulators can operationalize the Personal Data Protection Act, 2022 (with its 2023 implementing regulations) to give fintech, cloud, and AI investors the legal clarity they require, while the Tanzania Bureau of Standards aligns food, logistics, and metering rules with ASBF MOUs so exporters can unlock price premia in Asia.

A time-bound target makes this tangible: cut average port dwell time by 30–40 percent by 2028 and halve vessel waiting time to ≤5 days, metrics supported by port and maritime baselines, by tying customs, KYC, and e-invoicing reforms to standards harmonization across the EAC.

Trade and industrial policy complete the loop from rules to results.

The EAC Common external tariff’s 35 percent fourth band can be used as a lever rather than a wall: finished goods face the tariff, but capital goods and critical inputs enter duty-free when invested in Tanzanian assembly or processing for AfCFTA markets.

The next cabinet can put numbers to this industrial strategy by setting a 2030 target to double Tanzania’s exports to Japan and Singapore from their 2023 levels—raising combined sales by at least USD150–200 million—through AfCFTA-ready SEZs and supplier-development programs tied to Japanese and Singaporean OEMs.

If accompanied by port performance gains cited above, and by AfCFTA preference utilization, these export targets are achievable within normal productivity uplift ranges.

Resource governance needs similarly precise calibration.

Tanzania’s 16 percent free carried interest in mining is a durable statement of sovereignty, but rigid localization can deter high-tech entrants.

A Local Content and Technology Transfer Charter—with phased thresholds, joint labs, and tax credits for R&D and supplier upgrading—can preserve the 16 percent baseline while raising productivity.

The performance yardsticks should be explicit: 5,000 Tanzanians trained annually in mining/energy technologies by 2030 through co-funded programs and a +10 percent domestic-procurement share in qualified projects within three years of licensing.

These are realistic given the sector’s procurement volumes and the training pipelines embedded in many EPSA-financed projects.

If these reforms sound technocratic, the payoff is not.

A pipeline sized to capture 3–5 percent of EPSA6 plus two to three Singapore-backed equity platforms could mobilize USD0.5–0.8 billion per year into Tanzanian logistics, energy, and agro-processing between 2026 and 2028.

Port-time reductions of the magnitude targeted typically lift exporter realized prices by 2–5 percent and cut inventory costs by double-digit percentages, while BIT-enabled FDI in processing can raise the manufactures share of exports—a key marker of economic complexity.

Against a backdrop where Tanzania’s public debt is roughly half of GDP and tax revenues hover near 13 percent of GDP, shifting from debt-heavy infrastructure to blended, export-earning projects is not just prudent—it is necessary for durable growth.

Declarations only become development when translated into statutes, pipelines, and measurable results; otherwise, they remain talking points for the next conference.