COLUMN:THE CLIFF. BHP out, SPAC in: Can Tanzania still win?

IN 2021, three businessmen—John Dowd, Govind Friedland and Michael Klug—recognised a rising global opportunity: the rapidly growing demand for nickel, driven by the electric vehicle revolution and clean energy transition.

To seize this moment, they created GoGreen Investments Corporation, a Special Purpose Acquisition Company (SPAC). Unlike traditional companies, SPACs have no commercial operations; they exist to raise capital from investors and then merge with a promising private company to take it public more quickly.

GoGreen was incorporated in the Cayman Islands on March 17, 2021 and later listed on the New York Stock Exchange, raising roughly 240 million US dollars from investors keen on the greenenergy boom.

While GoGreen was forming, eyes were turning back to northwestern Tanzania, home to the Kabanga nickel deposit, one of the world’s most promising but underdeveloped nickel sulphide reserves.

The project had been dormant for years, constrained by infrastructure costs and lack of investment.

But in the same year 2021 the Tanzanian government signed a joint venture agreement with a relatively obscure UK-registered company: Lifezone Limited. Originally incorporated in Mauritius in 2008, Lifezone redomiciled to the Isle of Man on September 29, 2021 barely weeks before the Kabanga deal was formalised.

Lifezone brought a novel promise to the table: A cleaner, more efficient method of mineral processing called Hydromet.

Unlike traditional smelting, Hydromet uses water-based chemistry to extract nickel, copper and cobalt. The company touted the technology as a more environmentally friendly and cost-effective alternative to smelting.

However, at the time of the Tanzanian deal, Hydromet had never been used at industrial scale. Lifezone’s own investor presentations, filed with the U.S. SEC, confirmed that it had only been tested in pilot trials using samples of Kabanga ore in Perth, Australia.

Some pilot reports claimed up to 88 per cent nickel recovery, but these results came from small-batch experiments not from operating refineries. Despite the unproven nature of the technology, the deal moved forward.

A joint venture company, Tembo Nickel Corporation, was established 84 per cent owned by Kabanga Nickel Ltd (Lifezone’s project vehicle) and 16 per cent free-carried by the government. While the deal granted Tanzania an ownership stake, the project still lacked financial and technical heft to get off the ground.

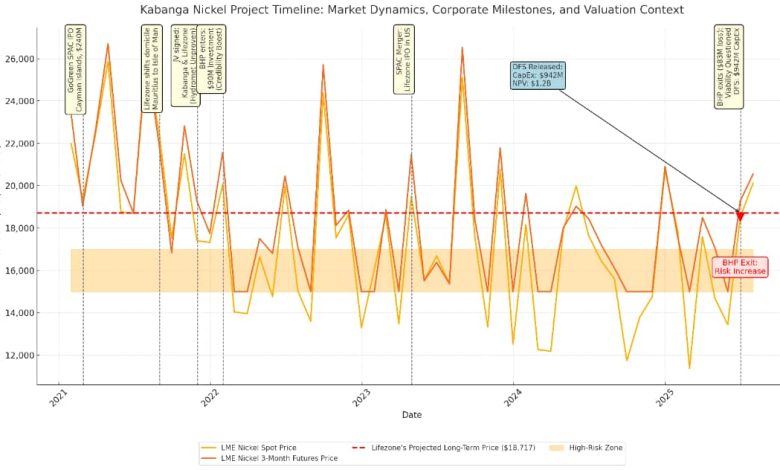

That changed in 2022, when mining giant BHP made a move that shifted the global perception of the project. BHP invested $90 million into Kabanga Nickel Ltd in two tranches, acquiring a 17 per cent stake.

The move gave the project much-needed credibility. BHP’s official statements called Kabanga “one of the best undeveloped nickel sulphide assets globally.” The involvement of such a heavyweight signalled to global markets that this wasn’t just hype.

This is when GoGreen made its key move. In 2023, it merged with Lifezone through a SPAC transaction, turning Lifezone into a publicly listed company under the name Lifezone Metals. The merger dissolved GoGreen and gave Lifezone access to the capital markets and visibility of a US-listed company.

The new structure placed the Kabanga deposit, the Hydromet technology, and Tembo Nickel’s majority control under a single public entity. The sponsors— Dowd, Friedland and Klug—had completed their financial engineering goal. But the timing and corporate registration trail raises eyebrows. GoGreen was incorporated in March 2021. Lifezone shifted to the Isle of Man in September 2021.

The Kabanga deal was also signed in late 2021. While there’s no evidence of illegality, the close alignment of these events suggests coordinated positioning, possibly designed to optimise regulatory benefits, tax structures or listing requirements.

Analysts say such synchronised activity is not unusual in high-stakes resource deals—but when combined with unproven technology and multiple offshore jurisdictions it raises transparency questions.

Then comes a twist. In July 2025, BHP quietly exited the project. It sold its 17 per cent stake in Kabanga Nickel Ltd back to Lifezone for up to 83 million US dollars – 7 million US dollars less than its initial investment.

The timing raised questions. BHP stated that its withdrawal was due to falling nickel prices and reallocation of capital in response to global market conditions.

However, BHP’s exit suggests more than market conditions; it may signal concern over the project’s viability or execution risk. This departure is thus destabilising via effectively removing the project’s key technical backer.

Indeed, when a major partner exits while absorbing a million-dollar loss, it’s wise to question what they truly saw coming. In response, Lifezone moved fast. On the same day as BHP’s exit, it published a report estimating 942 million US dollars in pre-production capital costs and 2.49 billion US dollars in life-of-mine costs.

The company projected annual output of 50,000 metric tonnes of nickel, with full production expected six years after construction begins.

A full Definitive Feasibility Study filed with the SEC outlined proven and probable reserves of 52.2 million tonnes grading nearly 2 per cent nickel and projected a net present value (NPV) of 1.2 billion US dollars using long-term nickel prices of 8.49 US dollars/lb.

Despite this show of confidence, fundamental questions persist. First, Hydromet remains unproven at commercial scale.

Lifezone’s own filings acknowledge that no refinery using Hydromet is yet operational anywhere in the world. Second, Lifezone Metals now lacks a global mining partner with the technical experience and resources to deliver such a complex project in a challenging location.

Third, the company’s network of corporate domiciles— spanning Isle of Man, Cayman Islands, Delaware and Tanzania—makes it harder for stakeholders to assess true ownership and revenue flows.

SPACs themselves add another layer of concern. While they offer speed and flexibility, they’ve also been criticised for bypassing some of the transparency and due diligence associated with traditional IPOs.

A 2023 Financial Times study reported that over 60 per cent of companies that went public via SPACs underperformed within two years. Critics argue that investor optimism is often based on projections, not proven results. Now Tanzania must make a critical decision.

The government still owns 16 per cent of Tembo Nickel. It has a strong interest in ensuring the project succeeds not just for revenues, but for the broader promise of industrialisation, job creation and global supply chain integration. But without BHP, the question remains: Can Lifezone deliver?

Mike Venance a fellow American-based analyst suggested that Tanzania could consider bringing in a new technical partner, or at the very least, renegotiate safeguards around performance benchmarks, timelines and community obligations. Others argue the country should insist on more transparent reporting, particularly regarding capital raises and offshore financial structures.

The Kabanga story is no longer just about geology but a case study in how global finance, technology hype and jurisdictional arbitrage intersect with African development ambitions. The presence of promising minerals is no longer enough.